A new perspective on determining best age of spay or neuter

Common sense disclaimer: As with everything that I write, it’s critical to seek the advice of a qualified veterinarian, preferably one that is board certified in theriogenology (reproductive science) for reproductive matters. This article and its contents are NOT designed nor intended to replace the need for a qualified veterinarian, but instead to help educate people to to work optimally with their veterinarians. All recommendations should be reviewed with qualified professionals, such as a board certified reproductive veterinarian, prior to implementation in a breeding program. Always seek the advice of your veterinarian.

There have been studies done that show both benefits and risk to spaying and neutering at a young age. Some results have not been fully presented in the media.

Desexing has both physical and behavioral implications. Spay/neuter timing needs to consider the both the physical and behavioral ramifications of allowing a dog to remain intact. I'll cover both here, and also present a risk analysis of physical issues associated with spay/neuter (S/N).Most families, however well-intentioned, are not prepared to deal with sexually mature dogs.

Both males and females can be fertile at six months of age. Many families don’t realize that dogs can even breed through many fences, so the longer you wait past sexual maturity to spay or neuter, the greater the risk of inadvertent breeding. Dogs previously not interested in escaping will suddenly find a way out of their yard when hormones hit hard and furiously.

Female behavioral concerns

Many families also are not comfortable dealing with multiple heat cycles in a female.

Females can cycle (in estrus, in heat, in season) as early as 6 months.

Heat cycles involve needing to keep their dog and home clean as well as protecting their dog from accidental breeding.

Dogs in heat should never go outside unsupervised, even in a fenced backyard.

They are more likely to try to jump or dig out, and many dogs are resourceful enough to breed through fences.

Even if a female doesn’t get out or breed through the fence, a resourceful male can often jump or dig in.

Females in estrus need to be thoroughly secured from any potentially intact (unneutered) male dogs for the full 21 days (plus or minus 7 days) of each heat cycle. Heat cycles typically occur twice a year.

Male behavioral concerns

Males can smell a female in heat from as much as a mile or two away and will be attracted to a female’s location.

Males are also prone to marking near a female in heat, so even if a female is secure, families can expect intact males near the home to want to be in the area and mark by urinating on or near the home.

Males often get frustrated and aggressive with other dogs when they detect a nearby female in season.

Males also increase in other behaviors when around a female in heat, including humping, escaping, roaming, spraying, and more.

Males can start to exhibit hormone-related behaviors at about 6 months of age. Hormone-related behaviors are less likely to occur if an intact female isn’t around. However, since a male can smell a female in heat from a great distance, then nearby females can impact the propensity of a male to spray/mark, escape/roam, hump, etc. Unneutered males should never be allowed to roam freely or be off leash in public.

It is not an exaggeration to say that even if a pet parent is walking with their dog and she is on leash that a male can breed her. A male can approach and be on a female before the handler realizes what is happening. When dogs breed, they “tie” together, and once a breeding starts, it can be over quickly and the male will “tie” with the female, meaning he will be attached to her for as long as 30 minutes or more. Trying to separate them at that point can be painful and damaging to both dogs. Besides, once the tie has started, it’s too late to prevent pregnancy.

The recent spay/neuter (S/N) research is the latest thing people are overreacting to without looking into the details. This can include some veterinarians.

There are studies showing both advantages and disadvantages to desexing, either at an early age or at all.

In general, we do agree that EARLY S/N should be avoided when possible.

However, shelters have been performing early (less than 2-3 months) S/N for decades and we have yet to see the epidemics people seem to be predicting when reading these studies.

The bottom line advice from the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) is due to the varied incidence and severity of disease processes, there is no single recommendation that would be appropriate for all dogs.[2]

So what do the studies really show?

A balanced review of the scientific literature was done by Dr. Jean Dodd, I’d recommend taking a look for yourself.[3]

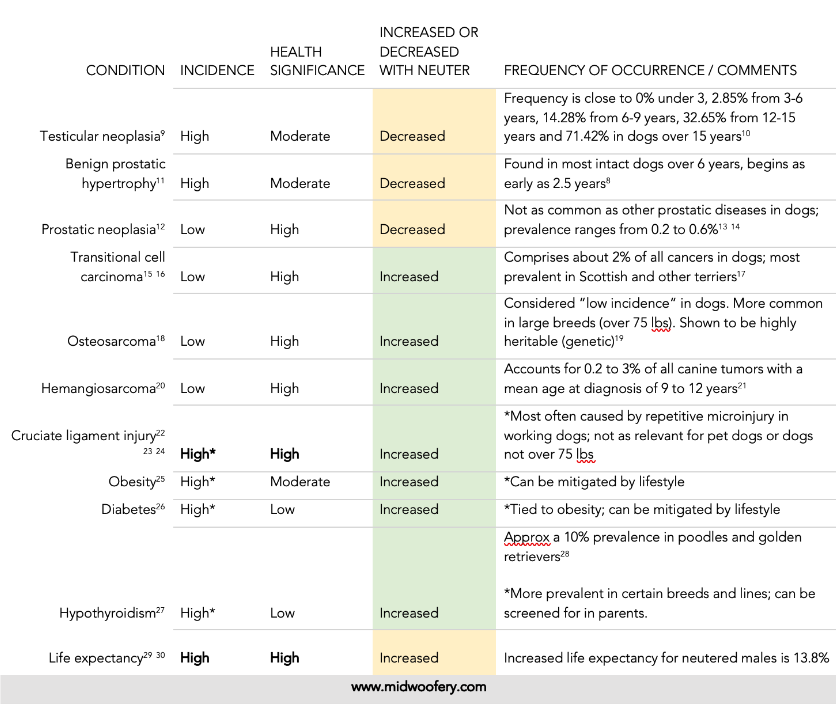

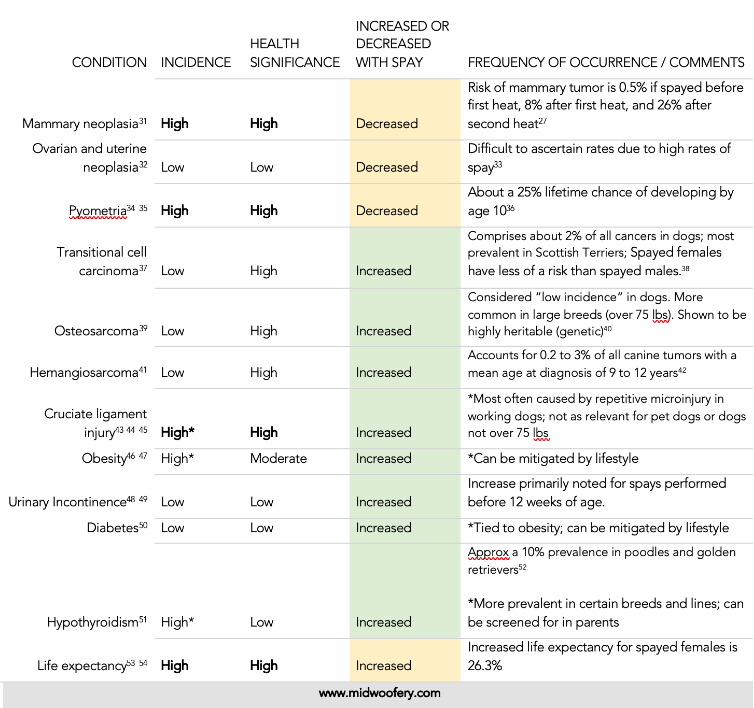

I’ve looked at the literature and compiled a risk matrix along with comments. Per the AVMA, it’s not appropriate to make a blanket recommendation for all dogs.

Based on what we have experienced in 30 plus years of breeding and training, we have NOT seen S/N associated problems in the breeds we have been involved in.

We have personally seen problems associated with late or no S/N. I personally have lost two dogs to mammary neoplasia, had another affected by it, and we have seen hormone-influenced cancers in other of our dogs. S/N will help prevent this.

Some of the risks can be mitigated by lifestyle, such as obesity and diabetes.

Most breeds in the S/N studies are LARGE breeds with large bred problems (joint problems, etc.). Those issues are much less likely in small or medium sized dogs (under 75 lbs), so, again, the individual needs to be looked at.

Many conditions mentioned in studies are found mainly in certain breeds and are NOT relevant to all breeds.

Incidence rates for some conditions are lower in all dogs, regardless of breed, and this should be taken into consideration as well.

The life-span issues should not be ignored as well: Intact dogs have a mean life expectancy of 7.9 years while desexed dogs have a mean life expectancy of 9.4 years.[4][5]

NOT covered in these studies are the lifestyle problems we see in unaltered dogs. Males hump, escape/roam, spray, and have some other undesirable behaviors when not neutered, and these don’t always go away when they are altered.[6]

Females also hump, bleed, escape, are more prone to metritis/pyometria (life-threatening uterine infections), and, of course, are at risk for pregnancy. Most pet families are not equipped to properly manage and care for fertile dogs.

Lastly, but importantly, most of the studies to date are problematic.

They are retrospective, which means that researchers can’t control or account for important variables such as diet, weight, lifestyle, owner’s economic status, and selection bias. They look at old vet records and draw conclusions from those.

For the most part these studies also only show correlation, not causation. Retrospective studies are good for finding areas that need further study, but not for drawing scientifically sound conclusions on which to make recommendations. Finally, most studies are only in one breed, which cannot be extrapolated to all other breeds.[7]

We recommend spay/neuter between 6 and 9 months for our puppies, based on what we know about their breed, size, and family histories. This allows the dogs to have some of the growth benefits of exposure to sex hormones while mitigating many of the risks, including behavior risks.

Also, given the mixed conclusions from studies, we feel this halfway approach is the most balanced for many dogs. And, per the AVMA recommendation, we also feel that each dog should be looked at individually within the context of its own risks and the lifestyle and needs of the family.[8]

How to evaluate risk

Based on the current research, I've compiled these matrices of conditions associated with both spay and neuter, as well as the rate of occurrence (incidence), the significance to a dog's health, whether it increases or decreases with spay/neuter, as well as comments including breed risk.

What you want to look at regarding risk is:

Does it have a high or low incidence?

Is there a strong health significance?

What is the frequency?

High risk plus high incidence is most significant

Low risk and low incidence is least significant

Again, you also need to pay attention to your breed and dog size as well to determine if the risk is even relevant

Conditions/Diseases Associated with Neuter

References: [9-10][12-30]

Conditions/Diseases Associated with Spay

References: [31-54] A 2020 analysis from researchers at the University of California Davis did a retrospective analysis of veterinary hospital records for 32 breeds and developed a list of recommendations for those breeds.[55] While that analysis does not cover all breeds or any cross breeds, nor does it include any behavioral or lifestyle considerations, it can be a good reference point for starting this discussion with your veterinary partners, who can take the whole dog into consideration.

The study covered joint disorders, cancers, IVDD, mammary cancer, and uterine infections. An interesting conclusion by the authors of this paper was that most breeder were clearly unaffected for joint disorders and cancers by age of desexing, although larger breeds had somewhat of a larger risk of joint disorders compared to smaller breeds. [55]

I very strongly recommend that you look up the specific references for your breed and situation from my tables as well as the UC Davis study and read those yourself. If you have questions, please be sure to print the papers and take them to your vet to discuss.

Surgical concerns

As I mention often, it’s important to see past individual data points and look at individuals. To help with this, I discussed this topic with several veterinarians to gain their perspective.

These veterinarians told me they base their recommendations on balancing the risks for the individual dog (per AVMA recommendations), but they also take surgical consequences into consideration in addition to the reasons I have outlined above.

Surgical risk for S/N increases with age, particularly the risk of bleeding. As the dogs mature, there is an increase in vasculature in the organs—more blood vessels. More blood vessels equal more bleeding. That increases the risk of internal bleeding in females as well as scrotal hematomas in males.

Additionally, healing time increases with age, so older dogs take longer to heal and may have more discomfort. One veterinarian stated she has a very strong dislike for spaying large breed females over 7 months old because of risk of complications.

References

[1] Pet Statistics. ASPCA, https://www.aspca.org/animal-homelessness/shelter-intake-and-surrender/pet-statistics, last viewed on 19 September 2019.

[2] Elective Spaying and Neutering of Pets: Gonadectomy Resources for Veterinarians. American Veterinary Mdical Association https://www.avma.org/KB/Resources/Reference/AnimalWelfare/Pages/Elective-Spaying-Neutering-Pets.aspx, last viewed 19 September 2019

[3] Revisiting Spaying and Neutering of Dogs and Cats. Dr Jean Dodds’ Pet Health Resource Blog https://drjeandoddspethealthresource.tumblr.com/post/125096705031/spay-neuter-dog-cat#.XIFXoRiZPdd. Last accessed 19 September 2019.

[4] Bushby PA. The optimal age for spay/neuter: a critical analysis of spay neuter literature. Presented at the Southwest Veterinary Symposium; San Antonio, TX; 2018

[5] Salmeri KR, Bloomberg MS, Scruggs SL, Shille V. Gonadectomy in immature dogs: effects on skeletal, physical, and behavioral development. J Am Vet Med Assoc1991;198(7):1193-1203.

[6] Hopkins SG, Schubert TA, Hart BL. Castration of adult male dogs: effects on roaming, aggression, urine marking, and mounting. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1976 Jun 15;168(12):1108-10.

[7] Bushby PA. The optimal age for spay/neuter: a critical analysis of spay neuter literature. Presented at the Southwest Veterinary Symposium; San Antonio, TX; 2018

[8] Bushby P. Breaking down the optimal spay-neuter timing debate. dvm360 website: veterinarymedicine.dvm360.com/breaking-down-optimal-spay-neuter-timing-debate. Published March 1, 2017.

[9] Hoskins, J. Testicular cancer remains easily preventable disease. Dvm360 website: http://veterinarynews.dvm360.com/testicular-cancer-remains-easily-preventable-disease. Published March 1, 2004.

[10] Santos, R. et al. Testicular tumors in dogs frequency and age distribution. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. vol.52 n.1 Belo Horizonte Feb. 2000

[11] Kutzler, M. Benign prostatic hyperplasia in small animals. Merck Veterinary Manual website: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/reproductive-system/prostatic-diseases/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia-in-small-animals.

[12] Bryan J. A population study of neutering status as a risk factor for canine prostate cancer. Prostate 2007;1;67(11):1174-81

[13] Feeney DA, Johnston GR, Klausner JS, Perman V, Leininger JR, Tomlinson MJ, 1987: Canine prostatic disease-compari- son of ultrasonographic appearance with morphologic and microbiologic findings: 30 cases (1981–1985). J Am Vet Med Assoc 190, 1027–1034.

[14] Levy, X., et al. Diagnosis of common prostatic conditions in dogs. Reprod Dom Anim 49 (Suppl. 2), 50–57 (2014)

[15] Bryan J. A population study of neutering status as a risk factor for canine prostate cancer. Prostate 2007;1;67(11):1174-81

[16] Panciera DL. (1994) Hypothyroidism in dogs: 66 cases (1987–1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 204 (5): 761–767.

[17] Knapp, D., Canine bladder cancer. Perdue University School of Veterinary Medicine website: https://www.vet.purdue.edu/pcop/files/docs/CanineUrinaryBladderCancer.pdf

[18] De la Riva G. Neutering Dogs: Effects on Joint Disorders and Cancers in Golden Retrievers. PLoS One 2013; 8(2).

[19] Bone cancer in dogs. AKC Health Foundation website: http://www.akcchf.org/canine-health/your-dogs-health/bone-cancer-in-dogs.html. May 10, 2010

[20] Zink MC, Farhoody P, Elser SE, et al. Evaluation of the risk and age of onset of cancer and behavioral disorders in gonadectomized Vizslas. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014;244(3):309-319.

[21] Clifford CA, Mackin AJ, and Henry CJ, (2000). Treatment of Canine Hemangiosarcoma, 2000 and Beyond. J Vet Intern Med, 14:479–485.

[22] Slauterbeck JR, Pankratz K, Xu KT, et al. Canine ovariohysterectomy and orchiectomy increases the prevalence of ACL injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;Dec(429):301-305.

[23] Whitehair JG, Vasseur PB, Willits NH. Epidemiology of cranial cruciate ligament rupture in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993;203(7):1016-1019.

[24] Torres de la Riva G, Hart BL, Farver TB, et al. Neutering dogs: effects on joint disorders and cancers in golden retrievers. PLoS One 2013;8(2):e55937.

[25] McGreevy PD, Thomson PC, Pride C, Fawcett A, Grassi T, Jones B. Prevalence of obesity in dogs examined by Australian veterinary practices and the risk factors involved. Vet Rec. 2005 May 28; 156(22):695-702.

[26] Nelson RW. Diabetes mellitus. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 6th edn. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO; 2005. p. 1563–9

[27] Panciera DL. (1994) Hypothyroidism in dogs: 66 cases (1987–1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 204 (5): 761–767.

[28] OFA Statistics by Breed website: https://www.ofa.org/diseases/breed-statistics#detail

[29] Bushby PA. The optimal age for spay/neuter: a critical analysis of spay neuter literature. Presented at the Southwest Veterinary Symposium; San Antonio, TX; 2018

[30] Waters DJ, Kengari SS. Exploring mechanisms of sex differences in longevity: lifetime ovary exposure and exceptional longevity in dogs. Aging Cell. 2009;8(6):752-755.

[31] Mammary tumors. American College of Veterinary Surgeons website: https://www.acvs.org/small-animal/mammary-tumors

[32] Waters DJ, Kengari SS. Exploring mechanisms of sex differences in longevity: lifetime ovary exposure and exceptional longevity in dogs. Aging Cell. 2009;8(6):752-755.

[33] Arlt, S et al. Cys c ovaries and ovarian neoplasia in the female dog – a systematic review. Reprod Dom Anim 2016; 51 (Suppl. 1): 3–11

[34] Egenwall A, Hagman R, Bonnett BN, et al. (2001) Breed risk of pyometra in insured dogs in Sweden. J Vet Int Med 15:530-538

[35] Wheaton LG. (1989) Results and complications of surgical treatment of pyometra: a review of 80 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 25: 563-568.

[36] Jitpean, S. et al. Breed variations in the incidence of pyometra and mammary tumours in Swedish dogs. Reprod Domest Anim. 2012 Dec;47 Suppl 6:347-50

[37] Panciera DL. (1994) Hypothyroidism in dogs: 66 cases (1987–1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 204 (5): 761–767.

[38] Knapp, D., Canine bladder cancer. Perdue University School of Veterinary Medicine website: https://www.vet.purdue.edu/pcop/files/docs/CanineUrinaryBladderCancer.pdf

[39] De la Riva G. Neutering Dogs: Effects on Joint Disorders and Cancers in Golden Retrievers. PLoS One 2013; 8(2).

[40] Bone cancer in dogs. AKC Health Foundation website: http://www.akcchf.org/canine-health/your-dogs-health/bone-cancer-in-dogs.html. May 10, 2010

[41] Zink MC, Farhoody P, Elser SE, et al. Evaluation of the risk and age of onset of cancer and behavioral disorders in gonadectomized Vizslas. J Am Vet Med Assoc2014;244(3):309-319.

[42] Clifford CA, Mackin AJ, and Henry CJ, (2000). Treatment of Canine Hemangiosarcoma, 2000 and Beyond. J Vet Intern Med, 14:479–485

[43] Slauterbeck JR, Pankratz K, Xu KT, et al. (2004) Canine ovariohysterectomy and orchiectomy increases the prevalence of ACL injury. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 429: 301–305

[44] Whitehair JG, Vasseur PB, Willits NH. Epidemiology of cranial cruciate ligament rupture in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993;203(7):1016-1019

[45] Torres de la Riva G, Hart BL, Farver TB, et al. Neutering dogs: effects on joint disorders and cancers in golden retrievers. PLoS One 2013;8(2):e55937

[46] Jeusette I, et al. Effect of ovariectomy and ad libitum feeding on body composition, thyroid status, ghrelin and leptin plasma concentrations in female dogs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl).2006 Feb; 90(1-2):12-8

[47] McGreevy PD, Thomson PC, Pride C, Fawcett A, Grassi T, Jones B. Prevalence of obesity in dogs examined by Australian veterinary practices and the risk factors involved. Vet Rec. 2005 May 28; 156(22):695-702.

[48] DeBleser B, Brodbelt DC,Gregory NG, et al. (2009) The association between acquired urinary sphincter mechanism incompetence in bitches and early spaying: A case-control study. The Vet J 187 (1): 42–47.doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.11.004.

[49] Beauvais W, Cardwell JM, Brodbelt DC. (2012) The effect of neutering on the risk of urinary incontinence in bitches - a systematic review. J Sm Anim Pract 53 (4): 198–204. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01176.x. PMID 22353203.

[50] Nelson RW. Diabetes mellitus. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 6th edn. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO; 2005. p. 1563–9

[51] Panciera DL. (1994) Hypothyroidism in dogs: 66 cases (1987–1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 204 (5): 761–767.

[52] OFA Statistics by Breed website: https://www.ofa.org/diseases/breed-statistics#detail

[53] Bushby PA. The optimal age for spay/neuter: a critical analysis of spay neuter literature. Presented at the Southwest Veterinary Symposium; San Antonio, TX; 2018

[54] Waters DJ, Kengari SS. Exploring mechanisms of sex differences in longevity: lifetime ovary exposure and exceptional longevity in dogs. Aging Cell. 2009;8(6):752-755.

[55] Hart Benjamin L., Hart Lynette A., Thigpen Abigail P., Willits Neil H. Assisting Decision-Making on Age of Neutering for 35 Breeds of Dogs: Associated Joint Disorders, Cancers, and Urinary Incontinence. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2020;7. DOI 10.3389/fvets.2020.00388